The Israeli American company StemRad recently presented to senior officials of the US Space Agency – NASA - the test data for the protective vest from the Artemis 1 mission. "The results have exceeded our expectations," Dr. Oren Milstein, the company's CEO and one of its founders, told the Davidson Institute website. "At first they sounded too good to be true, but after many months of thorough analysis of the data and consultation with experts from other bodies, we were convinced that the results were indeed that good."

The company was founded more than a decade ago, following the lessons learned from the accident at the Fukushima nuclear reactor in Japan. It was born out of the understanding that it is impractical to protect the entire body from radioactive radiation, and that in order to enable emergency teams to function, they must be provided with a solution that will protect the most radiation-sensitive areas of their bodies. These are mainly internal organs and the pelvic bone, which contains most of the bone marrow.

From here, the idea developed for a product that would provide similar protection to astronauts in space. Although they do not operate near a nuclear reactor that emits radioactive radiation, they may be exposed to high levels of radiation composed of charged particles emitted in large quantities from the sun, especially during periods of high activity, known as "solar storms". Unlike the lead protective vest designed to protect emergency crews on Earth from gamma radiation, the astronauts' vest, called AstroRad, uses compressed polyethylene, which absorbs charged particles like high-energy protons.

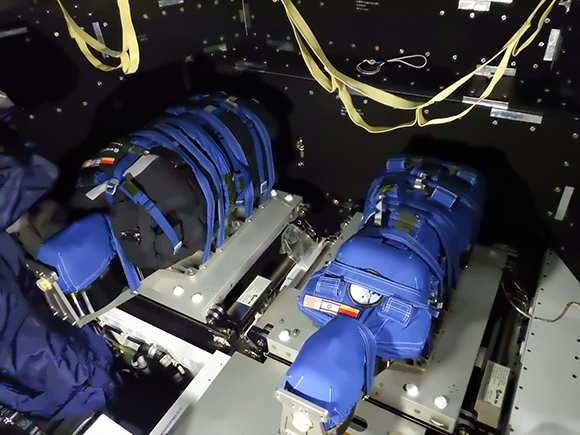

On the Artemis 1 mission, which took place about a year ago, an unmanned Orion spacecraft was launched on a 25-day journey around the moon, in order to test its functioning and its systems before the next missions in which astronauts will fly on it – first around the moon and later on the way to landing on it. In a joint initiative of the Israel Space Agency, the German Space Agency (DLR), NASA and the spacecraft manufacturer Lockheed Martin, two mannequins were placed in it, covered with many radiation sensors. The first doll, named Zohar, wore the protective vest, and the second doll, Helga, was left without it, as a control experiment. "Both were equipped with dozens of active sensors, on and inside the body, that measured and recorded radiation levels at every moment. Zohar had another set of sensors on the outside of the protective vest," explained Jordan Houry, StemRad's chief scientist in the experiment. "In addition, the dolls' bodies are networked with thousands of passive sensors, which measure the cumulative exposure to radiation."

During the Artemis 1 mission, no abnormal solar activity was recorded, so most of the radiation exposure occurred as the spacecraft passed through the Van Allen belts – areas rich in charged particles created under the influence of Earth's magnetic field, which protects us from much of this radiation. The raw experimental data showed that Zohar did indeed absorb much less radiation than Helga, but the data were limited because of the form of the experiment. For example, the mannequins absorbed almost no radiation from their backs, because they were seated facing forward, with their backs facing the spacecraft's service compartment, which absorbs most of the radiation.

So, the researchers used the data gathered to test in supercomputer simulations what protection the vest would provide for astronauts moving freely in the spacecraft. They also checked what would happen to them during strong solar storms. To this end, they also used data from two such storms, from 1972 and 1989, whose intensity was strong enough to endanger astronauts in space.

"According to our data, the level of radiation Zohar would have absorbed in the 1972 event is 60 percent lower than what Helga would have absorbed without the vest, and the difference is equivalent to about 1,500 X-rays," Khoury explained. "When we checked the protection of the pelvic bone, the main reservoir of bone marrow, the difference went up to about 90 percent."

During a solar storm, astronauts flying aboard the Orion spacecraft are supposed to huddle in an area of the spacecraft designated as a "radiation shelter." In fact, these are small nooks under the seats of the spacecraft, around which equipment and supplies can be arranged to provide them with optimal protection. The problem is that it will be difficult to stay in them for long hours continuously, let alone several days, and of course staying in them will restrict the astronauts' ability to carry out their routine missions.

The vest could allow astronauts, or at least some of them, to leave the shelter for a while and perform vital functions. StemRad emphasizes that it is not supposed to replace the radiation shelter in the spacecraft, but to complement it. Beyond the immediate protection, which will prevent injuries such as radiation sickness that will endanger the astronauts' lives, the vest reduces the level of radiation to which an astronaut is exposed, and therefore can allow an astronaut who was in space during a solar storm not to exceed the maximum level of radiation exposure, which will not allow him to embark on additional missions in space.

"After the first data indicated success, we did more than six months of additional analyses. Some of them were attended by experts from the National Laboratory in Oakridge, Tennessee, who will also co-author the upcoming papers," Milstein said. "I feel good about the results as a scientist, not just as a businessman."

The heads of StemRad and the Director General of the Israel Space Agency, Uri Oron, presented the data to Jim Free, deputy head of NASA and director of the Artemis program. "His response was, 'We couldn't expect better results,'" Milstein said. "In light of our success, we are exploring with NASA the possibility of reducing the mass of the vest in certain places, in order to optimize its use in space missions where every gram counts, without sacrificing most of the protection from radiation." According to Houry, a 50 percent reduction in vest mass would only offset 25 percent of protection, thanks to its design in which the thickness of the protective layer varies from region to region, depending on the risk level to the organs the vest protects.

"We are currently in a process with NASA, through the Israel Space Agency, on integrating the vest into the next Artemis missions. It is not certain that it will be in Artemis 2, which is a relatively short mission where the level of radiation exposure should not be high, but we are aiming to integrate it into Artemis 3, which is supposed to take humans to the program’s first moon landing, and of course in the missions that will follow."

The company is now working on optimizing the layers of protection. At the same time, they are working to improve the human engineering of the vest, in another experiment carried out in cooperation with NASA on the International Space Station. "Four NASA astronauts wore our vest at the station for long periods of time to test its ease of use for routine activities, including sleeping with the vest on. Astronaut Eitan Stibbe also did so on the 'Sky' mission last year," Milstein said. "The next step in development will be vests that can be adjusted in size and that fit the body of a particular astronaut, and of course with different models for men and women."

Meanwhile, on Earth, the company made its first major deal to sell protective vests to security forces, signing a contract to sell 360 protective vests to the U.S. National Guard for about $5 million. "The National Guard is somewhat analogous to the Home Front Command in Israel, and its personnel are supposed to provide a response in the event of an accident in a nuclear reactor, or, God forbid, an act of terrorism or a military attack with nuclear weapons," Milstein said. "The deal was agreed after very many tests they performed on our vest, and after a lengthy process that included working with Congress on budgeting for this protection. We hope that this will be the first of many deals, not only with the security forces but also with other emergency agencies, such as fire services, and of course with other countries around the world."

*

Itay Nevo is the editor of the website of the Davidson Institute for Science Education, the educational arm of the Weizmann Institute of Science.